The following extract is from the research paper Education, Knowledge, and Learning. An overview of theories and research about constructionism and making by Lorraine Charles, William Rankin, and Catherine Speight. You can download it for free here.

The ‘maker movement,’ like project- and problem-based learning, is another example of a learner-centric, active-learning methodology. Another form of constructionism, ‘maker’ education is based on learners developing an idea and then designing and creating an external representation of that idea. As with other constructionist approaches, it is learner driven, with learner agency at its philosophical core. However, perhaps more than any other constructionist framework, maker education emphasises “constructing knowledge through the act of making.”

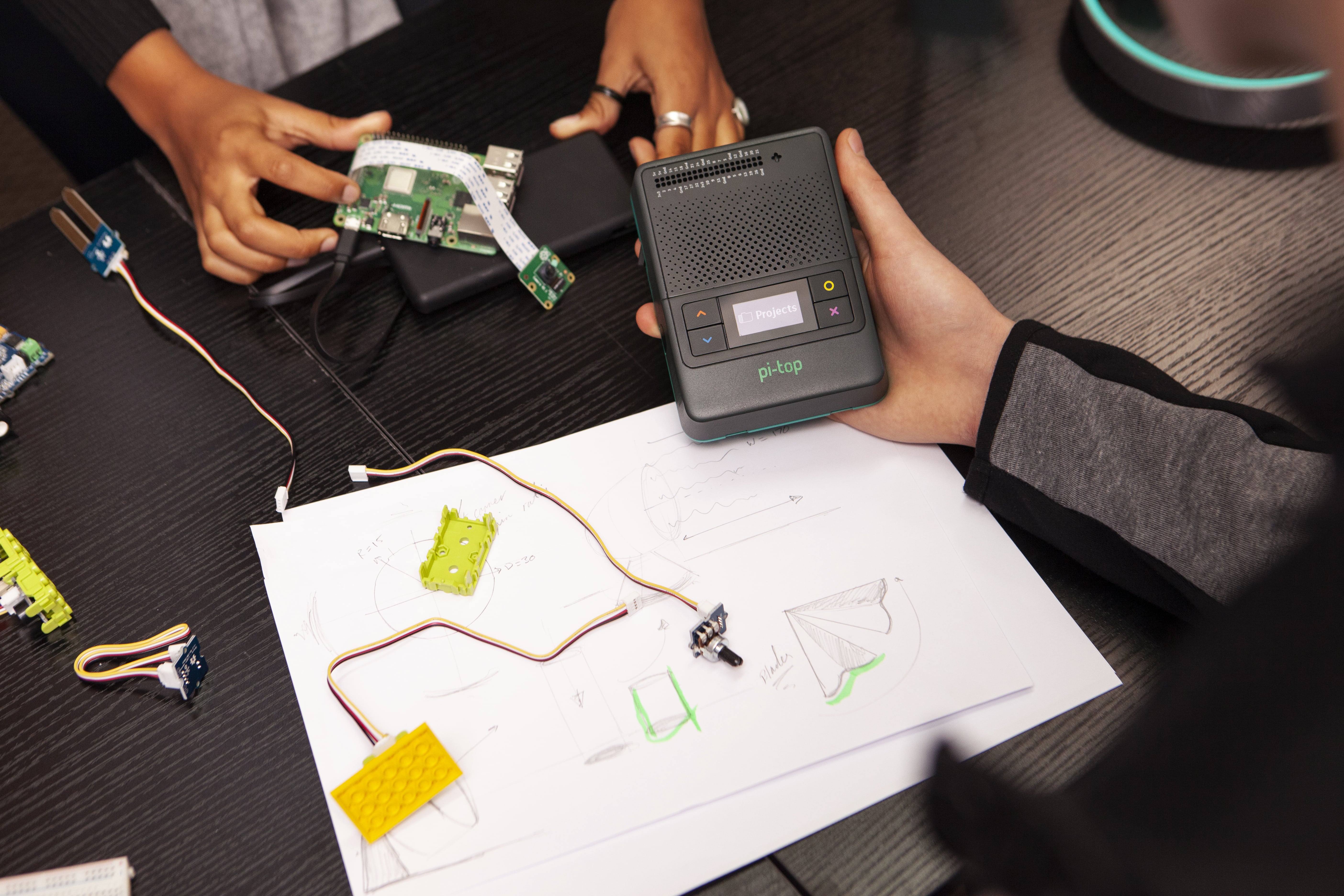

‘Making’ refers to a broad set of activities that can be designed with various learning goals in mind. It can take place in many kinds of locations that are collectively labelled ‘maker spaces.’ Classrooms, museums, libraries, studios, homes, or garages may all serve as maker spaces. As Fleming notes in her useful guide, what distinguishes these spaces is not where they are but how they are equipped and used: maker spaces offer access to tools and resources designed to empower learners who are working to turn knowledge into action. Additionally, more than either problem- or project-based learning, maker learning takes very seriously the social aspect of constructionism. As Donaldson argues “learning happens best when learners construct their understanding through a process of constructing [objects] to share with others.”

‘Making’ bridges the divide between formal and informal learning, challenging practitioners and educators to think more strategically and expansively about how learning happens

Maker learning has become more prominent in recent years, moving beyond long-standing associations of ‘making’ with vocational disciplines to encompass a broader segment of the learning spectrum. However, while the value of ‘making’ is well recognised, educators are still wrestling with ways to integrate this project into the more formal curricula that dominate most schools. Part of the reason for this friction is that ‘making’ bridges the divide between formal and informal learning, challenging practitioners and educators to think more strategically and expansively about where and how learning happens and making integration of this approach more difficult. Maker education’s blurring of the lines between formal and informal learning also means that some of the mechanisms with which schools have sought to measure or guarantee learning must be reconsidered. Traditional assessment systems, for example – designed largely to measure the accurate reception and replication of information delivered by teachers – typically lack a mechanism for tracking the learning that happens in the broader contexts of ‘making.’ Instead of an emphasis on assessing knowledge in the abstract – testing ‘knowledge as knowledge’ – ‘making’ requires a concrete demonstration of how learners are using knowledge or what they can do with the knowledge they have acquired, and this more holistic approach adds significant complexity to assessment.

Maker education works to prepare learners for the real world by giving them opportunities to approach, consider, and address real-world challenges of their own choosing, making whatever solutions or projects they feel are appropriate to do so. Because of this, as pioneer of the maker movement, Dale Dougherty, explains, when an individual generates a project, the project itself demonstrates what the individual has learned, and thus provides the best evidence of learning.

Maker education seeks to engender curiosity, tinkering and iterative learning, leading to more robust thinking through better questioning and more through ongoing exploration

Maker spaces are frequently informal, collaborative environments designed for creative production. Often associated with people working in the ‘STEAM’ disciplines (science, technology, engineering, arts, and mathematics), maker spaces encourage participants of different ages and levels of experience to blend digital and physical technologies as they explore ideas, learn technical skills, and create new projects. Maker spaces typically incorporate new technologies and innovative processes, encouraging participants to take advantage of these resources as they design and build. The essential characteristic of maker spaces is that they all involve and facilitate making, helping people develop an idea and construct it in some physical or digital form. In order to develop their projects, learners in these spaces must use a range of knowledge and experience holistically, often crossing disciplinary boundaries and learning to work with a range of tools, materials, and processes. By design, maker spaces are therefore ideal venues for the development of projects that do not fit neatly into narrow disciplinary or subject areas. They encourage learners to collaborate, remix, extend, and invent, often combining multiple approaches and knowledge areas in their projects.

By fostering this sort of multifaceted, multidisciplinary approach, maker education seeks to engender curiosity, tinkering, and iterative learning, leading to more robust thinking through better questioning and more thorough, ongoing exploration. As a learning approach, ‘making’ is designed to foster enthusiasm for learning, self-confidence, and natural collaboration. For this reason, community in the maker space serves as yet another crucial resource for the achievement of learning goals. Ultimately, the aim of maker education and educational maker spaces is the generation of learners who are determined, integrative, creative, critical, and intensively collaborative.

Article adapted from the research paper Education, Knowledge, and Learning. An overview of theories and research about constructionism and making by Lorraine Charles, William Rankin, and Catherine Speight. Version 2.0, January 2019. Download it for free here.

References can be found in the original text.