When the USSR launched Sputnik 1 sixty one years ago in October 1957, hotly followed by Sputnik 2 the following month, it signalled the start of the Space Race.

A key aspect of the satellites' scientific and propaganda success was the ability for amateur radio enthusiasts around the world to pick up its iconic beeping signal with their own homemade radio sets.

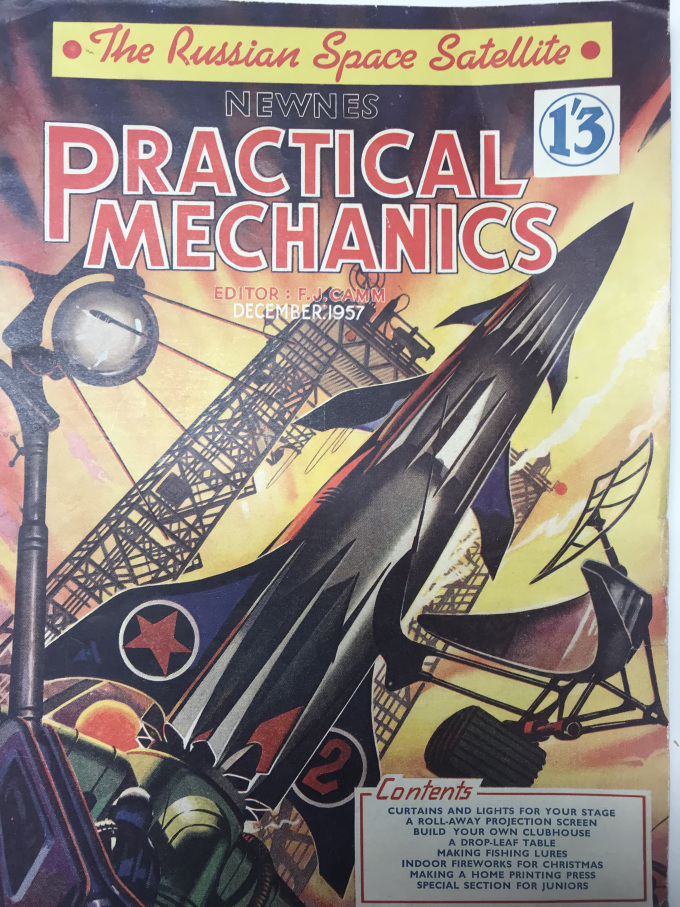

So by the December of that year magazines like Practical Mechanics were abuzz with leader articles detailing what little information could be gleaned from behind the Iron Curtain. With few details emerging you get the impression that the art department really went to town on the cover design.

The actual R-7 Semyorka launch vehicle was khaki green with four dumpy leg-like engines, rather than the sleek jet black instrument of death pictured here (Britain at that time remember, was still filling in bomb craters left by German V2 rockets).

Build your own TV for £10

Cold War propaganda aside, what’s also interesting about the December 1957 issue is the sheer amount of making projects contained within it. Sputnik heralded the age of cheaper amateur electronics, of wireless sets, early broadcasting techniques, and kits of components you got via mail order and made yourself.

One feature details how to build your own TV set for just £10 using ex-Government wartime surplus equipment. Companies like EMI and HMV were household names and ran what we’d now call Maker Days as well as offering kits and remote learning in subjects such as electronics, photography, and chemistry. In London, ham radio shops sprang up in Lisle Street and Tottenham Court Road, much like Internet cafes would do 50 years later before they too were swept away.

Maker projects

Yet it wasn’t all electronics content in the magazine. There are also more simple hobby-like projects too. Remember this was before the advent of mass consumerism, the era of mend and make do. If you wanted a pull-down projection screen, a drop leaf table or a motorised model of the Royal Yacht Britannia, you jolly well went to your shed and made it.

Page 126 reveals diagrams for ‘a glove dryer and stretcher’, under the sub-head of 'making a useful Christmas present’. Remember, wartime rationing of both food and materials, which had been in place since 1940, had only ended three years earlier.

Making isn't new

So what does all this nostalgia mean? Well, firstly it highlights that making, mending and creating things is certainly nothing new. As Bill Rankin, pi-top’s Director of Learning, says in episode one of our podcast "making and learning by that making is actually very old".

It’s how most people learnt throughout history, and we can track this maker mentality back all the way through Renaissance craftsmen and women to the monks and blacksmiths of the Middle Ages.

Granted the tools and technology have changed since the 1950s; we’ve moved on from valve-driven crystal sets and early TVs to Raspberry Pi powered laptops and LCD screens. But there are still familiar things drills, screwdrivers and hammers, and materials like wood, screws, and glue. Though you do wonder what a chap from the 1950s would make of a Formlabs resin 3D printer!

What's changed?

But the biggest changes are as follows. Firstly, we now have a better means of distribution. We have the ability to share plans and ideas globally, not just to male readers of specific publication based in the UK.

This allows us to work with people anywhere, and on anything. Those of you old enough to remember the dawn of the internet will probably remember the phrase, global village. We’re only at the start of exploring what this means for maker culture – global village blacksmith? It’s actually taken longer than we thought to lay the fibre and figure this out, but you can see the potential in everything from Instructables to Scratch to WikiHow

"Everyone’s grandfather worked in a factory; each generation, fewer do "

The second thing may take even longer to come to fruition. It’s about owning the means of production. As we rapidly approach the point where it’s cheaper and easier to design and make everything from my own mobile phone cover to swimming pool controller, what does that mean for the future of work? When we all have access to production systems and open shared knowledge of how to use it, what will the the future of manufacturing look like? There are whole industries built on supplying us with stuff or moving that stuff around, what happens to them?

"The next generation of manufacturing wisdom is more likely to bubble up from local experiments than trickle down from legacy institutions"

Why this matters

The skills we learn through making, whatever our age, give us both options and opportunities. With rising economic divide and a growing gap between the haves and the have nots, having a broad skill set ensures you have at least some control of your own destiny.

As we heard from Mark Stevenson in episode 5 of our podcast, the world is facing a huge number of really big problems from environmental collapse to AI taking your job. Consequently, jobs of the future might actually be the ones we make ourselves. They may not even be called jobs, but a blend of interests, hobbies, callings and passions. We’re seeing this already in sites like Esty and thegrommet.com, which help makers take their products to a global market.

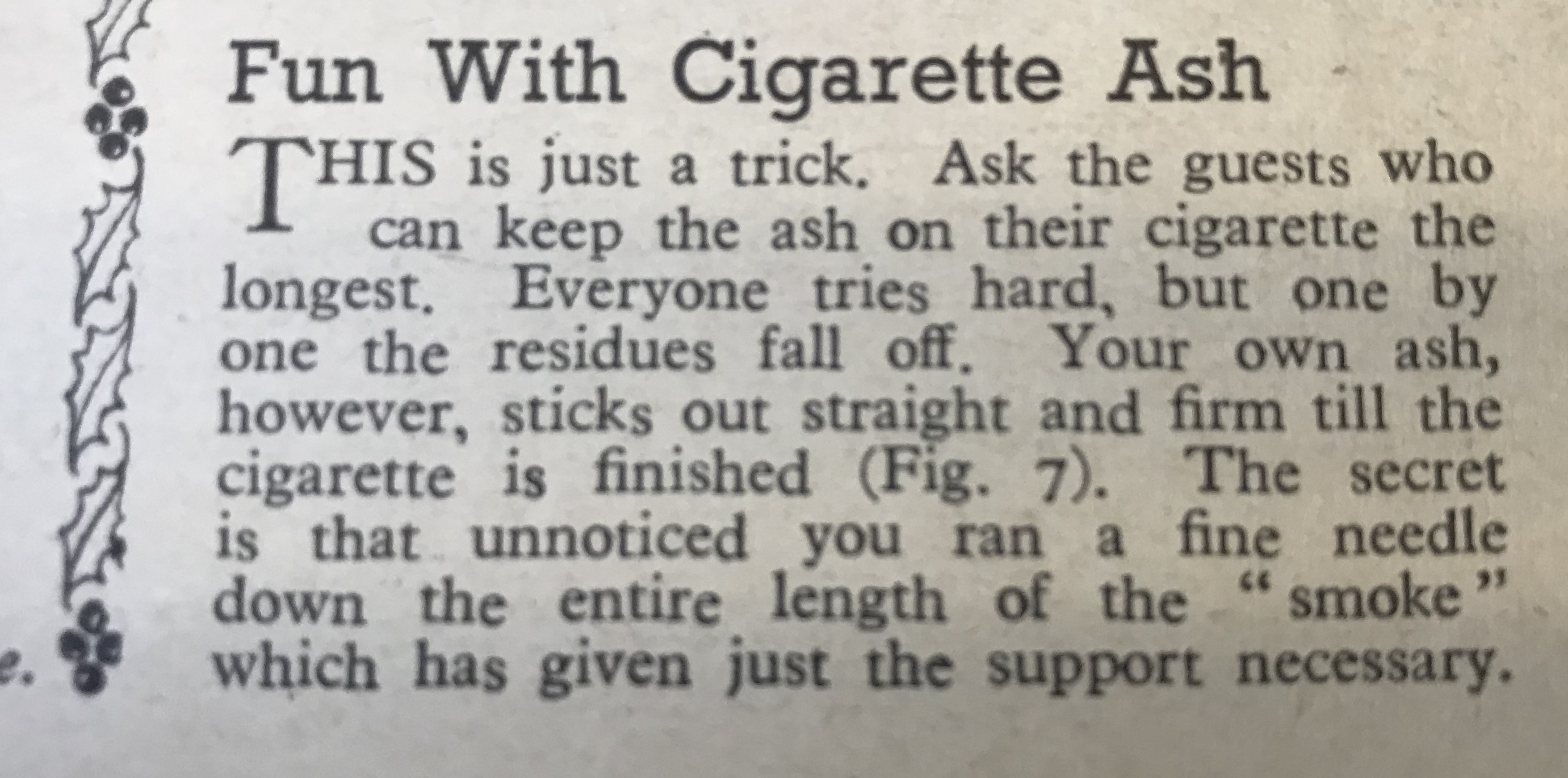

But as it’s Christmas, for the final word let's head back to our historic copy of Practical Mechanics and a feature entitled 'Tricks for Christmas’. Here we find ‘Fun with Cigarette Ash’ as one of the suggestions for keeping guests amused during the festive season. Some things have changed after all, Merry Christmas!